Editors’ note: An earlier version of this article was published in Vol. 104, No. 1 of The Pinion, with slight revisions made for this publication.

After more than twenty years, Hawaiian language classes have returned to McKinley High School, giving students the opportunity to once again study ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi as part of the world language electives.

Grounded in the Nā Hopena Aʻo (HĀ) Framework, the return of Hawaiian language classes is part of the Hawaiʻi Department of Education’s broader effort to incorporate Hawaiian culture, history, and language into public school curricula. The program combines structured Papa ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi lessons with opportunities for students to engage with cultural practices, local traditions, and community resources.

Lehua Brown, Complex Academic Officer for the Roosevelt-McKinley-Kaimuki Complex Area said to The Pinion, “Hawaiian Studies embraces the culture, language, history, practices, beliefs, values, skills, and the deep interconnections between ʻāina, wai, lani, and kānaka.”

By integrating language study with an understanding of Hawaiian values and history, the initiative aims to provide a more comprehensive educational experience that reflects the heritage of the islands and strengthens students’ connections to their communities.

“Learning and appreciating these relationships provides a foundation not only for those native to this land, but for all who call Hawaiʻi home,” said Brown.

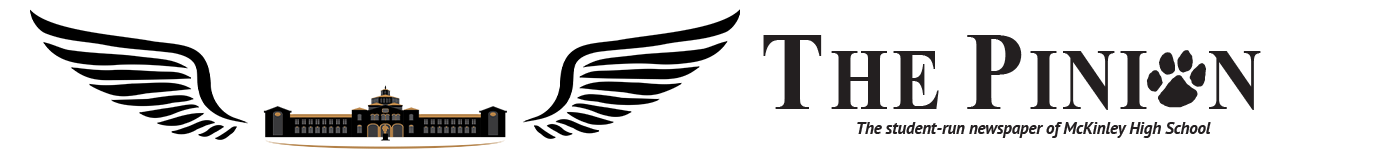

Kumu Kuaanaai Lewis, who has taught English as a Second Language since 1993, begins each ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi class by leading students in singing Hawaiʻi Ponoʻī, connecting them to the state’s history and traditions from the first moments of class. He works with students on pronunciation, gestures, and cultural practices, integrating hula, mele, and other aspects of Hawaiian culture alongside language instruction.

“Seeing students engage with Hawaiian and connect with their heritage shows how language can bring people together,” Lewis said. “It’s about more than the classroom—it’s about community and identity.”

Following the overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani in 1893 and the contested annexation of Hawaiʻi by the United States, Hawaiian was banned in schools and discouraged in public institutions. For much of the 20th century, students were penalized for speaking Hawaiian, and Native Hawaiian culture and identity were marginalized.

“Because ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi was discouraged for so long, teaching it today goes beyond vocabulary and grammar,” Lewis said. “You don’t have to be native to enroll in the class. The goal is to help students understand the culture and history of our islands and share it with the broader community.”

For students, the return of ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi provides an opportunity to reconnect with the language and culture of the islands and explore their own heritage. Kainani Reverio ‘26, said the program has given her the opportunity to engage with her father’s Hawaiian roots and communicate with her grandmother in ways she never could before.

“I’ve always wanted to know more about my culture,” Reverio said. “Now I can finally learn words and understand stories that were just in my family. I feel more connected to where I come from.”

“It makes me proud of my family and my history,” Reverio added.

Kimo Kaio ‘28, grew up in a family where Hawaiian culture was not emphasized, but his relatives encouraged him to explore it through school. Through the program, he now passes phrases and cultural practices to younger family members. “It’s like I’m passing something on that I almost didn’t have,” Kaio said.

Through the program, Kaio has not only learned the language but also gained tools to connect his family and community to their heritage. He shares phrases and cultural practices with younger relatives, helping them understand traditions that were once distant in his family. “I didn’t grow up speaking it, but now I’m helping my cousins and friends know who we are,” he said.

Beyond his own family, Kaio sees the potential for Hawaiian language programs to foster cultural pride more broadly. “If more schools had them, imagine how many students could feel this pride,” he said. “It could change communities across the islands.”

Equity in access to Hawaiian language programs remains a central focus across the state. Schools offering these courses receive professional development, curriculum resources, and funding support, while partnerships with community practitioners and educators help expand opportunities for students.

“Schools like McKinley embracing Hawaiian Studies represents a full circle,” Brown said. “From a time when students were punished for speaking Hawaiian to now, when it’s celebrated and shared across the campus—it’s a powerful shift.”

For Reverio and Kaio, the program has already sparked a sense of purpose and belonging. “It’s more than just learning a language,” Reverio said. “It’s about healing and understanding ourselves.”

As Hawaiian returns to McKinley High, each chant, step, and phrase represents a quiet act of reclamation, Lewis said. The program not only honors the past and engages students in the present, but also provides a model that could be implemented in other schools to expand access to Papa ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi across the islands.

“It’s generational thinking,” Lewis said. “We’re planting seeds now that will grow for future students. The language carries the people—when students speak ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi, they carry their ancestors with them.”