Litter Bearer Strives For Opportunities

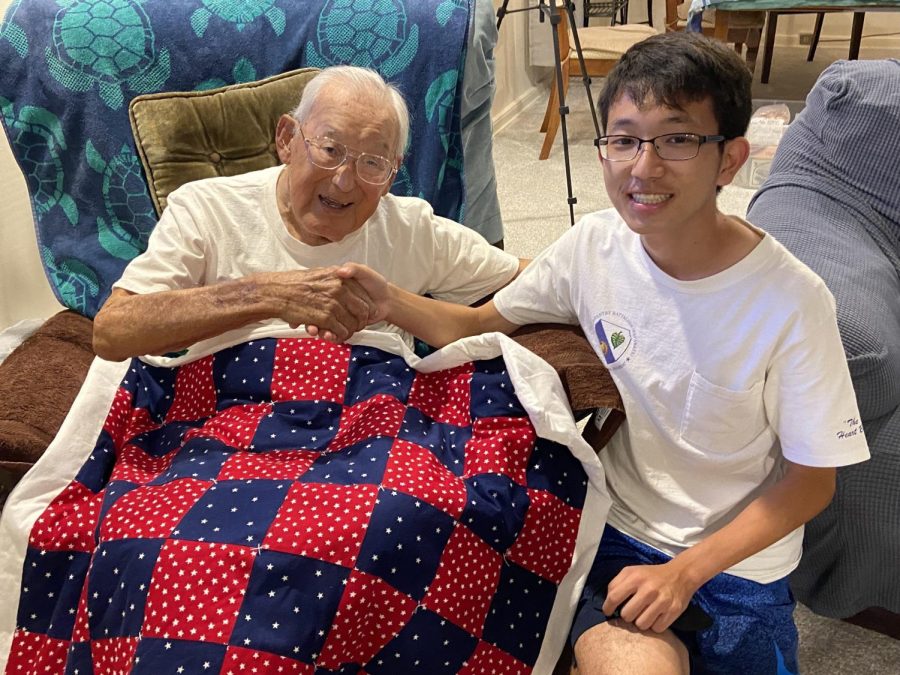

By Photo by Beverly Yoshioka, daughter.

Takashi “Taka” Manago thanks Shane Kaneshiro for making a quilt for him.

May 3, 2023

Japanese Americans were discriminated against and not trusted when Pearl Harbor was attacked by Japan on Dec. 7, 1941. Although the soldiers of the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team were sent to Europe to fight for the United States, loyalty had to be proved with the risk of their lives.

On a Sunday afternoon, sitting in front of me was 99-year-old Dr. Takashi “Taka” Manago, who was a staff sergeant in the 100th/442nd RCT as a litter bearer, a soldier who transports casualties with stretchers from the front line to the medics.

Stories were unveiled in his soft-spoken but spirited voice, describing his life and the opportunities presented to him.

Born Jan. 20, 1924 in Captain Cook, Hawaii, Manago was the fifth child to Kinzo and Osame Manago. Manago’s parents were the founders of the Manago Hotel in his hometown and is still open to this day, having 106 years of operation. On the day Pearl Harbor was bombed, Manago was 17 years old and a senior in Konawaena High School.

“I thought my father and the hotel would be confiscated,” Manago said.

However, Manago added, “My family, we were fortunate.” The hotel was closed to the public and housed military personnel during the war, so they were able to keep the hotel running.

After graduating from high school in 1942 he attended University of Hawaii at Manoa for a year and a half until being drafted on Sept. 18, 1944, and sent to train at Camp Hood, Texas.

With a mischievous smile, Manago shared a story that, not intentionally, deceived his captain,

“My brother called my captain and said ‘This is Major Manago. My brothers are stationed at Camp Hood. Can you give my two brothers a pass (leave).” Following direct orders and without hesitation, captain gave his consent. “I had a nice time with my brother,” Manago said.

Upon returning, the captain asked Manago, “What branch is your brother in?”

Manago chuckled and responded, “He is not affiliated with any branch, that’s his given name, ‘Major Manago.”

After basic training, Manago and his brother traveled to New York then transferred to France by boat. Manago meeted up with the 442nd RCT and join the 100th Infantry Battalion, Able Chapter (A Company) in Marseille, France. As his company was on their way to Italy, someone on the boat contracted measles. They were quarantined at Leghorn (Livorno), Italy.

For the next three weeks after being quarantined, Manago would served as a litter bearer during the historic mission to break through the German Gothic Line. In the dead of night, Manago and his partner searched for the casualties.

“My part of the war is to go to the front where the GI were hurt out there and come back,” Manago said. “Too dangerous to go during the day… The German was shooting at us, we got (shot at by) the Ak Ak (88mm gun).”

While on duty in Milan, he saw the Domm de Milan where he said it was untouched by the war. He also was given boxes that would have sweets, soap, cigarettes and chewing gum. There was a demand for it. Manago said he sold them for $10 each to the Italians. Manago whispered “Black Market.”

As the war ended, Manago went to Sweden where he learned how to ski and to take upon the opportunities to visit Italy’s atmosphere and beautiful buildings such as the Vatican church.

Manago reenlisted another year in Italy because he knew this was an opportunity that is once in a lifetime to be in Europe.

“No one shooting at me, the war is over,” Manago said.

Manago pursued his education in general medicine from the University in Florence in Italy where he would meet his first wife, then returned home. In 1956, Manago earned his degree at Creighton University in Nebraska and continued on at Fairleigh Dickinson University Dental School.

As a veteran that served as a replacement for the 100th/442nd RCT and experienced combat for only three weeks, Manago said he felt he did not contribute to the war and his story as a soldier was irrelevant. However, the importance of his journey to broaden his experiences after the war in Europe and to take advantage of the educational opportunities to become a dentist is what stood out to me.